by Catriona

Funny you should ask that. I only just gave a class on "setting" last month, for the first time. Preparing for it, I thought more about how much of what goes where than I ever have in all my years of writing. (When you're an extreme pantser, you only think about how to write when you've agreed to teach a class. It was the same with "clues". I was as surprised as anyone about what came out.) If it's okay with you, I'm going to mine that workshop for this blog, because I'm flat out, pre-Bouchercon, and pre-book launch.

Agreed? Thank you.

So. Susan, Frank and Cathy have said everything there is to say on how much detail and what kind. I'm going to concentrate on where the details go.

There’s a

case to be made for an honest to God paragraph, or even page, of description. If it’s done well and if there’s a little something extra in

there - some humour, or some tension, or

some light on character – why not?

Well, one reason why not is that there’s a

case to be made for slipping details in on the fly. You build up a rich picture just the same and you don't wreck the pace e.g. of a thriller.

But I don't think it matters anyway. When the

reader turns the last page, she or he won’t be able to remember how it was

done, if it was well done. She or he will only remember the immersion in a

fully-realised world. (I wanted to use Renee James’ Seven Suspects as an

example of fantastic setting – Chicago, the working of an upscale hairdressing

salon, and the world of young homeless people – but when I went back

to the book, I found that she does it so subtly I couldn’t pick out an example. (That’s

some of my favourite kind of writing: where you can’t catch them at it!))

In short, I'd say by all means spread a blanket and lay that detail down. And by all means

do it in pinches. But there’s one thing I don’t think you

should do, and that’s sneak in details where they don’t belong.

Where's that? I'm glad you asked.

If you say “The house was cold.” you're admitting that you’re describing the setting. You’re taking a whole

sentence to do it. It’s honest writing. But if you try to shoe-horn a bit of description into a sentence that’s doing something else, it can go wrong.

"There were

ten rooms in the cold house." is weird.

"It was cold

in the ten-roomed house." is worse.

At some point we need to decide whether we're writing a story or selling real estate.

“A

thundering iron gate fell nearby .... The parquet floor shook”

“Her blood

gushed out in gouts that stained the tufted carpeting”

How terrible are those two sentences? Who cares whether the carpet is tufted when someone's blood is gushing out in gouts? What is it with floors?

I'm going to end with one of my favourite quotes from one of my favourite writers. Jane Austen, tongue firmly in cheek, had this to say about putting things where they belong. She was writing to her sister, and responding to some sour reviews of Pride and Prejudice, written by some mightily ruffled and extremely displeased male (don't roll your eyes: it's just a fact) reviewers who thought she was getting too much praise.

"The work is rather too light, bright and sparkling; it wants shade; it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, with solemn, specious nonsense about something unconnected with the story; an essay on writing, a critique of Walter Scott, or anything that would form a contrast..."

And to think some later critics seriously reported that she regretted the tone of her masterpiece. They probably think Robert Frost is a big fence fan too.

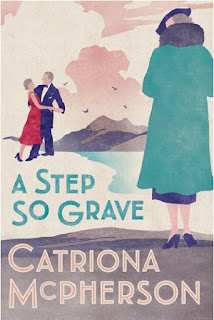

And while you're here . . . No they're not updating the Matrix, I really do have another book coming out next week after that one that came out last week. A STEP SO GRAVE (Dandy Gilver No.13) is out in the US on Tuesday. You can order it here.